For Michelle Simes-Kennedy , type 1 diabetes (T1D) is more than a professional focus—it’s a personal reality she has navigated for more than two decades. As a clinical social worker, Simes-Kennedy has spent much of her career helping young people and families understand and manage chronic health conditions, including her work at the Mary and Dick Allen Diabetes Center at Children’s Hospital of Orange County. There, she developed programs to guide adolescents with T1D through the often-daunting transition into adult care. Now serving as a full-time leader at Breakthrough T1D, she brings both her clinical background and lived experience to the forefront of conversations about access, stigma and support.

In her conversation with ABILITY Magazine’s Chet Cooper, Simes-Kennedy reflects on why T1D is recognized as a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act, how accommodations can empower students and professionals and why embracing available resources doesn’t have to conflict with personal identity. Simes-Kennedy underscores the importance of reframing T1D, not as a limitation, but as a context—one that shapes how individuals engage with the world while still pursuing their goals and aspirations.

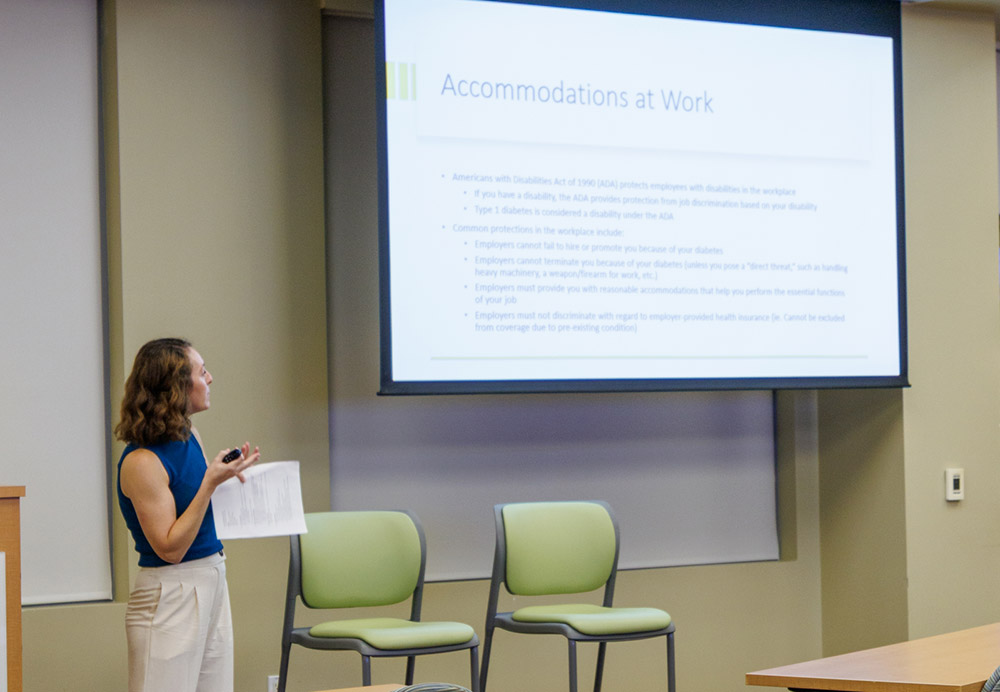

Chet Cooper: Can you talk a bit about T1D and how it relates to the ADA?

Michelle Simes-Kennedy : Sure, my background is as a clinical social worker, and I’ve been in outpatient practice for many years. A lot of where I come from has been talking with kids and families over the last 10 years, working with chronic condition populations. I’ve worked with kids with autism, I’ve worked with kids with neurodevelopmental conditions, as well as I work in the T1D clinic on the CHOC side (Children’s Hospital of Orange County) within the Mary and Dick Allen Diabetes Center. Throughout that time, my goal as a social worker working in that capacity for the last about 10 years, has been to make the clinical concepts accessible and digestible to kids and families. When I was working in that role at CHOC in their endo clinic with the type 1 population specifically, I was developing the program to transition paediatric patients to adult care, essentially, and to give them a streamlined way of doing that to mitigate against dropping off in adult care. I say all of that to give some background as to the way that I talk about T1D, which is often geared towards young adults, so a perhaps less engaged population. My goal is always trying to make things more accessible and understandable.

Cooper: What do you mean by less engaged?

Simes-Kennedy : In clinical practice, a lot of my experience is talking with teens or young adults in the type 1 population. Speaking to my role as a social worker in that type 1 clinic for a few years, it was a lot of work around understanding that my identified patient population was this young adult cohort. Technically, anyone ages 12 and up to age 25. But the goal was taking this clinical information and turning it into something that was understandable to let’s say, 16, 17, 18-year-olds, 19, 20, 21-year-olds who perhaps most of them at that point in their lives—I think like any of us at that age–engagement in our health care isn’t a top priority.

Typically, it’s not the most exciting thing about being a late teen young adult. So, trying to discuss T1D in a real concrete accessible way with this population has been a really interesting challenge that I’ve enjoyed. I think all of that to say, talking about T1D as a disability, I think, is the goal because we, myself included—I’ve had type 1 for over 20 years.—We all need to understand the system that we’re operating within and the context that we exist within so that we can navigate it successfully. And a part of doing that, as it relates to accommodations of someone with T1D in particular, the American Disabilities Act has certain language, certain criteria, that different organizations abide by.

Part of that is stating that people with disabilities can receive certain accommodations; and T1D has been described as being a disability. I know from personal experience, from working with patients, that many people don’t agree with labelling themselves as having a disability as it relates to the type 1. I completely respect anyone’s relationship to their T1D, and at the same time, try to give them the knowledge of the broader system that we’re all navigating, and how can we leverage it so that we can take advantage of the things that are available to us.

Cooper: Do you transition the way you speak about this information, based on if you are talking to parents or teens and/or young adults?

Simes-Kennedy : Yes. Typically, I like to get the sense of who the audience is. So, at the talk at Hoag, I asked the room as to who had taken advantage of accommodations, who knew what accommodations were. And then also got a sense of who, in the audience, had T1D themselves and who was a parent, which helps me to get a sense of what the needs might be for that group from the talk that I’m giving. I like to include different examples or different language to make the points a little bit more salient depending on who the audience is.

Cooper: Back to the ADA and disability, how did you navigate the stigma and bias around being considered to have a disability?

Simes-Kennedy: I think it’s a few things. The ADA is just a player in this broader landscape that we’re all, as people with type 1 or not with type 1, but any other condition that they’re navigating. We’re all trying to figure out how we can succeed in whatever we’re trying to do. I have often found myself talking about accommodations specifically, mostly as it relates to school and, usually, as it relates to going off to college. The way that I conceptualize that is that (it) is a huge shift in a family’s life. That’s a huge shift in a young adult’s life. They’re now going off, they’re going to be in charge of a lot of this daily management that perhaps they weren’t in charge of previously. And just like any of us, when we are navigating any life transition.

Whether you’re 10, whether you’re 18, whether you’re 35, whether you’re 65, there are things that are going to be changing. Thinking about something concretely, for example, going off to college, I like to highlight what supports are available to us. As a social worker, I’m always like, “What are our strengths here? What are the protective factors that can help us through this transition?”, whether it may be challenging inherently or not. Some of that is looking at the university or the college itself to see what they offer first and foremost in terms of accommodations, in terms of support to make that transition easier for someone with T1D.

I am not a part of the ADA. I think referencing their language and the things that they outline is helpful and useful because you can learn to use that to your benefit. So, whether you’re advocating for brand new accommodations—Perhaps, the university is not versed in what a T1D accommodations are.—you can bring in the verbiage that the ADA has. You can bring in this bigger entity within this country that you can have to support your request for additional support. I think all of it, ultimately, comes down to whether you feel comfortable describing yourself with type 1 as someone who has a disability or not. Me personally, I’m less interested in that. I think to each their own. My interest lies in how we can leverage the supports that are available around us and understand the context to which all of those exist so that we can navigate this more easily.

Cooper: Where did you start with your social work?

Simes-Kennedy : I got my undergrad in psychology. After my undergrad, I went to Cal State, Long Beach. I did a program called AmeriCorps for 10 months with this inaugural partnership with them and FEMA. I ended up doing a 10-month program driving across the country several times in a van, doing disaster relief and recovery efforts around the country. That program was my first experience seeing what different communities are like and getting to meet people completely different from where I’ve come from and really hearing and seeing what needs there are out there. And that’s what prompted me to pursue my master’s in social work.

So, after that, I went and got my master’s in social work at Fordham University in New York City. That program was really focused around social justice and how to make things equitable and accessible to communities and paired that with my interest in health care. I’ve had T1D since I was 13. My type 1 diagnosis predates all of this. For almost everyone that I’ve known, I think their T1D has played a role in the way that they’ve pursued work or educational opportunities. So, at the end of my master’s program, I did a fellowship in healthcare. It actually was in palliative care and hospice, but that was an entryway into the healthcare system as a social worker.

Then the rest is history. I got connected after that to working at NYU Langone in their school of medicine within their child and adolescent psychiatry department, working with kids and families with autism. I love that population. I worked there for a few years and developed some education and programming and then moved to Southern California.—I’m from here originally.—Moved back here, got connected to CHOC and started in their endocrine division working with their T1D patients on that transition from paediatric to adult care program. Then, within CHOC, there’s a newer autism centre outpatient program.

Cooper: Thompson?

Simes-Kennedy : Thompson, yes! I was there for several years and actually left there this April to join Breakthrough T1D full-time.

Cooper: What would you like the general public to know about T1D?

Simes-Kennedy : I will just say, from personal experience, having worked with patients for the last 10 years and now working in a non-profit setting that’s not only really research-driven, but it’s also globally-driven and globally connected, has been a really interesting experience. To see T1D from a micro level, the individual level—what people are doing, how people are experiencing that daily—to, now, the macro systems level of how communities and groups and different cultures are engaging with T1D has been a really unique and incredible learning experience to be a part of, to continue to gain insight holistically into the type 1 community.

Cooper: Do you know You’re Just My Type?

Simes-Kennedy : Yes. Laura. I went to diabetes camp with her. It’s a small world!

Cooper: Did you get to meet Mary and Dick Allen?

Simes-Kennedy : I don’t believe I met Mary, but Dick stopped by the clinic when I was working there at some point. He was lovely. He was really, really wonderful.

Cooper: Do you use Dexcom or Tandem? What are you using?

Simes-Kennedy : I use the Omnipod 5 and the Dexcom G7.

Cooper: Why did you choose the Omnipod?

Simes-Kennedy : I chose the Omnipod because when I had my first child—I have two kids.—The first time I got pregnant in 2019, I didn’t want to have a huge tubing system just coming out of my maternity pants, to be quite honest. That was my decision making at the time. I was fortunate enough to be working at that time in the T1D Clinic at CHOC. My colleagues who are now dear friends had all of this wealth of knowledge as to the different pumps and stuff that were out there, which led me to the Omnipod. Previously, I’d been on the same Medtronic pump for forever.

Cooper: Do you know who Earl Bakken is?

Simes-Kennedy : I don’t.

Cooper: So, Earl Bakken created the pacemaker, and then he created the first pump, which is the Medtronic. The irony of this guy—who I got to spend time with in Hawaii.—is he had a pacemaker himself as he got older. So, he created something, he invented something that later in his life he needed. He also had a diabetic pump. I wanted to share that story of how bizarre that his life was. He’s passed away a few years ago now.

Simes-Kennedy : Wow, yeah. That’s amazing.

Cooper: You haven’t tried any tandem products yet?

Simes-Kennedy : I have not, no. I hear good things.

Cooper: Dick Allen basically helped create the tandem. He did that because of his granddaughter.

Simes-Kennedy : I will say it’s something about the T1D community at large, whether you’re working professionally in that space or you’re just connected via having it or a family member with it, I think that there really is something to the power of a parent or a grandparent, specifically, and what they can accomplish. I think the most incredible things that I have seen come to fruition have been initially powered by parents or grandparents of kids with T1D.

Cooper: I think in almost all movements, you need champions, and what better champion than a loved one that the needs of your support?

Simes-Kennedy : Yeah, it’s incredible.

Cooper: Do you know who Mary Tyler Moore is?

Simes-Kennedy : I do know who she is.

Cooper: How do you know that? You’re too young to know that.

Simes-Kennedy : We were big fans of the classics in my house growing up.

Cooper: Do you know her connection with the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (now Breakthrough T1D)?

Simes-Kennedy : Yes, she had type 1.

Cooper: I interviewed her a long time ago now. When I was asking her questions, I was clueless of what I was saying, which I’ve done a couple of times in interviews connected to Type 1. I recently got Type 1 about a year ago.

Simes-Kennedy : Oh, you I did? Can I ask how that experience was for you? What prompted that?

Cooper: I got it from the immunotherapy treatments I’ve been getting for the last multiple years for cancer.

Simes-Kennedy : That’s a huge adjustment, and unexpected.

Cooper: It’s frustrating. In this meeting this morning, there were five people on the interview, and my alarm kept going because my Dexcom expired, and it doesn’t like that, right?

Simes-Kennedy : Yes!

Cooper: I was trying to move my phone away as far as possible and while I’m talking, I’m inserting a new Dexcom, and then I’m trying to get rid of the old one. You know the trick, you have to get rid of the other one and move it about 20 feet away.

away.

Simes-Kennedy : What are you on, the G7?

Cooper: G7, yeah. I’m using the Mobi, finally. I know there’s a wire, but the sucker is smaller. You almost forget, and you’re able to get the insulin so much easier. There are so many people where their vision is not the best, so for them to have to put a needle into the insulin vial and then suck it out. I was having problems actually getting to the centre of the vial with the needle, but with the Mobi, they created a system that you don’t to do any of that. It’s unbelievably cool technology. The engineers that came up with that kudos to them. Do you know anything about that?

Simes-Kennedy : I don’t know about all of them, but I went to a conference and got to see some of the new things out there, including the Mobi. I know a few people who went on to it as a trial, and I’ve only heard really good things about it, which is great.

Cooper: No, it’s crazy the way they made it so much simpler, so much lighter, one-fourth the size. It’s smart. I did have to buy an iPhone. I wasn’t an iPhone fan. At least for the phones. I now have to carry around two phones because I’m not getting rid of my Android. Other than that, it’s pretty good. I feel so lucky to be able to experience all this later in my life. Because most people get it when they are young, and then the mental health issues of people that get it at an early age, I definitely can understand that.

Simes-Kennedy : Yeah. I think it’s tough at any point in time, but for you to view it as something that you’re grateful for because of the access to the technology now, I think that that’s huge.

Cooper: Knowing that so many people go through this every day in their lives. —I’ve had an incredibly rich, experiential life traveling around the world and doing so many things, and I still ride a motorcycle. I still surf, but you have to think about it, and you have to think about, “Okay, I’m going to go surf there. I know it’s not the best condition of the water. This little clip, is it really going to keep anything out of my body?”

Simes-Kennedy : It’s always your brain is always thinking simultaneous to anything that you’re doing.

Cooper: Can you give a little background of the 180 decisions and how they came up with that?

Simes-Kennedy : Yeah, that’s a really good question. That came from work that Breakthrough T1D did. They had it in some really nice marketing campaign they did for T1D awareness. They had this really nice video about the mental burden that T1D can have. There was this video of people always keeping this balloon up in the air for the entire day as they’re doing things. The balloon being held up in the air was the metaphor for their T1D management while they’re simultaneously on a meeting, doing an interview, doing whatever they’re doing.

I think it’s important to talk about all of the decisions that our brain is making, either consciously or subconsciously, as someone’s type 1. Especially with having had type 1 for so many years, I think that my brain is used to operating in this pretty intense capacity, largely unconsciously. I think I’m making decisions on doing math equations in my head, which is not my strong suit, but things that can really have quite a big impact on my health, while I’m simultaneously trying to achieve things educationally, professionally in my life. So, I think that reminding all of us with type 1 or people around us that on average, we’re making 180 additional decisions a day is important to put into context.

Cooper: It is definitely something that you have to be proactive about. You have to change your sites. You have to monitor what you eat. You have to calculate what you’re eating, and you have to bolus. You have to monitor that.

Simes-Kennedy : I think it’s so interesting because it causes people with type 1 to become aware of our biology and our anatomy, whether we ever ask for that opportunity or not. Now, we’re thinking about our metabolism and our digestive system and how a protein impacts us versus a carbohydrate versus sugar. Those are things that most people are not thinking of, and now we are always considering them, even if we’re not acting on them. Then also what are the consequences, practically, if we are misjudging a bolus (a dose of insulin taken to handle a rise in blood glucose), and then also emotionally and psychologically, if you misjudge a bolus, does that lead to greater blood sugars? Does that lead to a greater A1c? Could we potentially feel like we are therefore directly causing our future complications? It really can snowball in a person’s mind without them really being aware of the magnitude of having type 1 sometimes.

Cooper: Have you ever experienced where you might be having a bad day, bad sleep because of that bad day, and then the reaction to your levels from not sleeping well or having a nightmare or something like that?

Simes-Kennedy : It’s interesting because, only lately, have I given myself some time and space to look at my T1D like a player in my life. I’m a middle child. I have a competitive nature. Whether competing against myself or others, to be the top of my class, the top athlete. I just have that in me, and I really have never looked at my T1D as an explanation or a path as to if I’m not feeling up to whatever it is, an assignment or being ready for race day when I did cross country. I never really incorporated T1D into my thinking. I just took care of it. I have always been well-controlled for one reason or another. It’s always just been there side by side with me doing its thing. Perhaps it’s coinciding with now working in the fully T1D organization. But now, I’m finally giving myself the space to see how a 300 blood sugar for several hours overnight could impact the way that I function for a 7:00 AM meeting. To be honest, it’s a newer practice that I’m engaging in.

Cooper: If I’m correct in what I’ve heard from endos (endocrinologists), those that can’t produce the insulin might still have insulin in their body?

Simes-Kennedy : I think there are a lot of variables. Genetics play a factor there, at which stage you got diagnosed with T1D and did you still have different things that were working in your body? Was your body still producing a little bit of insulin, either for a long time or maybe not so long? Cortisol stress impacts all of us differently. Our adrenaline impacts us all differently. There are a lot of different variables, which is, I think, why it’s so hard to put your finger on why things are happening. There are so many variables that are coming into play that it’s not like you just get to go to the endo and you get a prescription for perfect 24/7 blood sugar and you go home. It’s a constant wheel that you’re trying to navigate, but also at the same time live a life outside of just managing type 1.

Cooper: What’s your perfect measurement? 110?

Simes-Kennedy : Oh, gosh. I would say if I am within range for a majority of the day and I don’t feel totally exhausted by my T1D, that feels like a win. For me, personally, I am all about balance and looking at a picture holistically. Having a target blood sugar doesn’t really help me to achieve that, if that makes sense.

Cooper: Are you typically in the 150s-160s, or do you not even look anymore?

Simes-Kennedy : I definitely do look. I think that it’s important and it’s useful to have targets because those clinically help us to determine, “Are you at higher risk for complications? Are you at lower risk for complications? How are you going to do long term?”. Those are really helpful guidelines. I actually don’t know my parameters off the top of my head because I’m not really motivated personally by specific numbers.

To give some context, I have two kids. My youngest is a year and a half old. During pregnancy, you have to keep your numbers so tightly controlled that, for me, it was not quite all-consuming, but it really took up a lot of my mental energy to make sure the numbers were controlled, to make sure I was getting them in tight range. Because the insulin needs of someone who’s pregnant vary every single day, and they get increasingly more as the pregnancy goes on. Sometimes, I would eat five almonds, or when I woke up in the morning, I’d have to go and do several squats or run around to bring my blood sugar down because for some reason, my blood sugar would skyrocket. I think that moving away from that tight, tight control, and not being in pregnancy anymore, my goal is to be within what’s clinically recommended, and also to realize if I’m outside of range, that it’s also okay and that I have confidence that I’ll be back in range again at some point.

Cooper: When you’re talking about the pregnancy, I know there’s some complications that could occur, but just the additional stress of just trying to stay in range cause you to be out of range because of the stress.

Simes-Kennedy : It’s like an impossible task. Yes.

Cooper: The children are good?

Simes-Kennedy : The children are good. They’re healthy. Healthy pregnancies, healthy deliveries. They are thriving. They’re a year and a half and five years old. But yeah, it took a lot of work and a lot of focus to get them here as someone with T1D.

https://abilitymagazine.com/living-and-thriving-with-type-1-diabetes/

No comments:

Post a Comment